Searching Techniques

| Developed by Hardeep Singh | |

| Copyright | © Hardeep Singh, 2000-2009 |

| seeingwithc@hotmail.com | |

| Website | SeeingWithC.org |

| All rights reserved. | |

| The code may not be used commercially without permission. | |

| The code does not come with any warranties, explicit or implied. | |

| The code cannot be distributed without this header. | |

Problem: Given a list of distinct numbers (LIST), and another number (A), find the index of A in LIST if it is present or indicate that it is not present.

Although we have narrated the problem for numbers, it can actually refer to any datatype that can be compared for equality and arranged in order, such as strings.

Note: In the text below, lg(n) means log of n to base 2.

Solution #1: The naive approach

The simplest way, of course, is to compare the given number to each of the numbers in the list. If a number in the list matches the given number A, we can return the index of that number. If we reach the end of the list, we can indicate that A does not exist in LIST. Here is an implementation of this simple algorithm:

#include <stdio.h>

#define MAXELT 50

int main()

{

int i=-1,n=0,list[MAXELT],a;

char t[10];

int linear_search(int list[],int n,int a);

do { //read the list

if (i!=-1)

list[i++]=n;

else

i++;

printf("\nEnter the numbers <End by #>");

fgets(t,sizeof t,stdin);

if (sscanf(t,"%d",&n)<1)

break;

} while (1);

printf("\nEnter the number to be searched for >");

//read the number

scanf("%d",&a);

int pos=linear_search(list,i,a); //do linear search

if (pos==-1) //print the result

printf("\nThe number does not exist in the list.\n");

else

printf("\nThe number exists at location %d.\n",pos+1);

return(0);

}

int linear_search(int list[],int n,int a)

{

int i;

for (i=0;i<n;i++) //step through the list

if (list[i]==a) //if found, return

return i;

return -1; //else return not found

}

//Note that we did not even need to store the numbers in a list in this

//case. We could have kept comparing as we received. However, if multiple

//searches are to be done on a single list, this is not possible. In this

//case, we used this method to ensure conformity with other methods to be

//shown next.

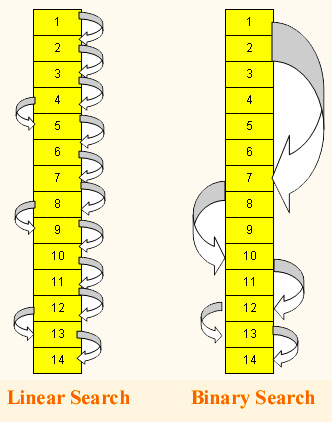

Since this algorithm compares the given number to all N elements of the list, it is an O(n) algorithm. Due to this reason, this algorithm is known as Linear Search.

Better search algorithms do exist and we will come to that, however this one is quite flexible: it doesn't require any restriction on the order in which numbers appear in the input list. So it can be used even if the list is not sorted or if the medium on which the list is stored requires sequential access (eg. Tapes).

Solution #2: Binary Search

This algorithm goes as follows (it requires a sorted list in input, unlike the previous algorithm):

An implementation of the algorithm is given below:

(Here, we show only the changed function binary_search. The rest of the program is the same as in linear search, just change linear_search function with binary_search and change all references to linear_search.)

int binary_search(int list[],int n,int a)

{

int first=0,last=n-1,mid;

while (first<=last) { //iterate while first<=last

mid=(first+last)/2; //calculate mid=trunc((f+l)/2)

if (list[mid]==a) //found

return mid;

else if (a<list[mid]) //not found - look in the

last=mid-1; //upper half of list

else

first=mid+1; //look in lower half

}

return -1; //return "not found"

}

Some people also implement binary search in the following recursive way:

int binary_search_dash(int list[],int first,int last,int a)

{

int mid;

if (first<=last) {

mid=(first+last)/2;

if (list[mid]==a)

return mid;

else if (a<list[mid])

return binary_search_dash(list,first,mid-1,a);

else

return binary_search_dash(list,mid+1,last,a);

}

return -1;

}

Although this is a more direct implementation of the above description, it uses more stack space compared to the first implementation, and is much slower on most systems. Also, this form of recursion is called 'Tail Recursion', which is the worst form of recursion. Recursion is a powerful tool which must be used with care. Recursion is advised only in certain cases, where it does not impose unnecessary action, as in Quicksort.

Binary search is O(lg(n)) as it halves the list size in each step. It is a large improvement over linear search; for a list with 10 million entries, while linear search will need 10 million key comparisons, binary search will need just about 24. Although binary search is already very good, at times it can be slightly improved, lets see how.

Solution #3: Fibonacci Search

Who does not know about Fibonacci numbers? They crop up in so many diverse problems that can't even be listed! From estimation of the number of rabbits in successive generations, to the number of leaves on branches, fibonacci numbers have far-reaching uses. In future Seeing With C might feature a write-up on different ways of generating them, here we will see ways of using them! (Generation of Fibonacci numbers is another misuse of recursion.)

The fibonacci series has 1 as the first two terms and each successive term is the sum of two previous terms. So, it goes 1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,44,...etc. Each number appearing in the fibonacci series is called fibonacci number.

Fibonacci search changes the binary search algorithm slightly: instead of halving the index for a search, a fibonacci number is subtracted from it. The fibonacci number to be subtracted decreases as the size of the list decreases.

Have a look at its implementation:

int fibonacci_search(int list[],int n,int a)

{

int f1,f2,mid,first,index;

f1=1; f2=0; mid=2; //initialise the first two fibonacci

//numbers. F1 will be the main

while (f1<n) { //set F1 to a number >= n

f1=f1+f2;

f2=f1-f2;

mid++;

}

f2=f1-f2; //set F1 to the largest number <=n

f1=f1-f2;

mid--;

first=0;

while (mid>0) { //loop

index=first+f1;

printf("\nfirst:%d,index:%d,f1:%d,list:%d,mid:%d,a:%d",first,index,f1,list[index],mid,a);

if (index>=n || a<list[index]) {

mid--; //if the number is bigger, move back

f2=f1-f2; //to a smaller fibonacci number

f1=f1-f2;

}

else if (a==list[index]) //found: return the index

return(index);

else {

first=index; //if the number is smaller, move to the

mid=mid-2; //second part of the list and

f1=f1-f2; //reduce F1 back two F-numbers

f2=f2-f1;

}

}

return(-1); //bad luck: not found

}

Whew, this one has the longest code so far. It is also O(lgn) algorithm.

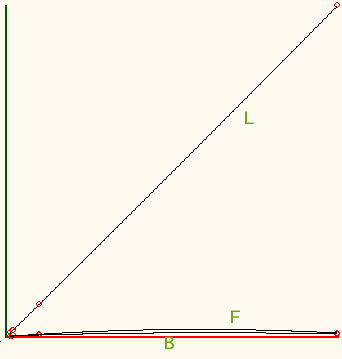

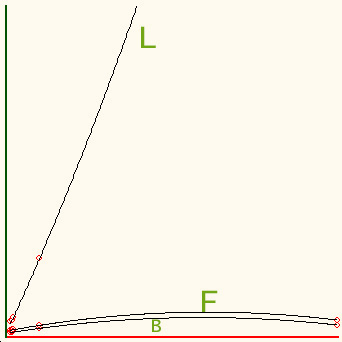

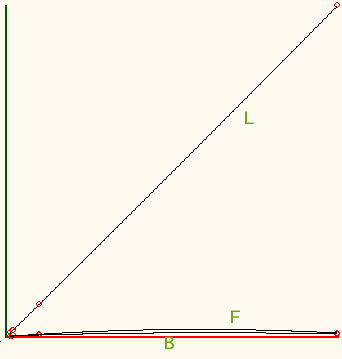

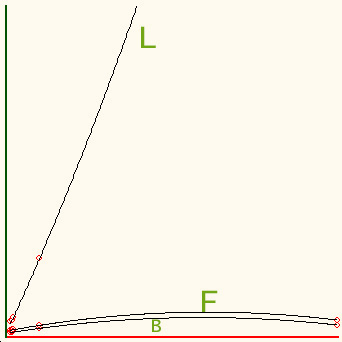

In order to compare the three algorithms shows, we

did a small test, on six lists with sizes varying from 15 to 1000. On the same

list, we performed four searches each - a mix of existing and non existing

numbers. The first list was not sorted - hence the result from binary and

fibonacci searches were expected to be wrong. The number of comparisons

carried out by each algorithm was tracked.

The following graphs show the comparison - the first one the left shows the

result from a single individual search, and the second cumulative from all

searches:

|

Its obvious that Binary search is the best of all (for sorted

data, of course) - however the margin with Fibonacci search isn't huge.

So what is Fibonacci search useful for? One of the key advantages with Fibonacci

search over Binary search is that comparison dispersion is low, so for example if

Binary and Fibonacci searches just compared element 100, and Binary search

now compares element 200, Fibonacci search will now compare element 150. This means

that for mediums that are accessed sequentially, especially tape drives, Fibonacci

search makes more sense.

ADDENDUM

In this part, I will express the linear and the binary search algorithms in 80386 assembly language. This, is towards the following goals:

Linear Search

Precondition: CX holds the number of entries, SI has been initialised to first array element, D=0.

AGAIN: LODSD ; The instruction reads the next number from memory

; into a CPU register(EAX)

CMP EAX,EBX ; Compare registers EAX and EBX. EBX already holds

; the value to be found

LOOPNE AGAIN ; Loop if EAX and EBX Not Equal and all entries have

; not been exhausted - to statement labeled AGAIN

CMP EAX,EBX ; Out of the loop - Two things are possible: EAX and

; EBX were found equal, or all list entries exhausted

; So, compare to make sure

JNE LABEL1 ; Jump if Not Equal to LABEL1

... ; Code to announce the fact that the entry has been

; found at location marked by CX and exit

LABEL1:... ; Code to announce that the number has not been

; found and exit.

Binary Search

AGAIN: MOV AL,FIRST ; Register AL <- Memory location containing FIRST

CMP AL,LAST ; CoMPare AL (FIRST) with LAST

JA NOTFOUND ; Jump if Above - to NOTFOUND since FIRST>LAST

ADD AL,LAST ; ADD LAST to AL. Al now contains FIRST+LAST

SHR AL,1 ; SHift Right AL once, this will divide it by 2

MOV MID,AL ; Send current value of AL to memory location MID

MOVZX AX,AL ; AX <- AL. (This is called MOV Zero eXpanded)

SHL AX,2 ; SH Left AX by 2. This multiplies it by 4. This is

done because each array value is of $ bytes.

ADD AX,OFFSET ARRAY

; Now AX contains the address of MID element

MOV SI,AX ; SI <- AX

LODSD ; Read value from memory location SI into EAX

CMP EAX,N ; CoMPare EAX with N, the number to be found

JE FOUND ; Jump if Equal to FOUND

JL LESS ; Jump if Less to LESS (to lower list). Note that

; no comparison is done here, just a jump. Just one

; comparison was done in CMP statement above. The flags

; hold the result which is checked by the jump

; instruction. Jump is equivalent to a simple goto

; in high level language; it does not do any inherent

; comparison

MOV AL,MID ; AL <- MID

DEC AL ; AL <- AL-1

MOV LAST,AL ; LAST <- AL. These three instructions accomplish

; LAST=MID-1.

JMP AGAIN ; Iterate

LESS: MOV AL,MID ; AL <- MID

INC AL ; AL <- AL+1

MOV FIRST,AL ; FIRST <- AL. These three instructions accomplish

; FIRST=MID+1

JMP AGAIN ; JuMP

FOUND: ... ; Code to indicate "Found number" at location contained

by SI and exit

NOTFOUND: ... ; Code to indicate "Not found"

That's all folks!